A number of Army documents and memoirs written by infantrymen in the European Theater of Operations shed light on what combat troops carried in their pockets

Infantry replacement Alexander H. Hadden arrived on the frontlines near Weiswampach, Luxembourg in November 1944 carrying a field pack containing two wool blankets, a complete change of winter clothing, a few days' worth of rations, mess kit, and his personal belongings. Hadden estimated that he was carrying approximately forty-five pounds of equipment. When ordered forward with his new company Hadden noticed the spontaneous shedding of gear, an anathema to Hadden who had been thoroughly schooled by the Army in "the sanctity of this equipment, and in the need to care for and preserve it." As the march progressed:

I became aware of items of gear underfoot and along the wayside. I was preoccupied by the anguish of my own aching muscles, however, and gave them little mind. . . Gasps and moans of distress were soon heard on all sides. Beads of sweat poured down my face. Before long there was a veritable cascade of equipment falling to the roadside, no mention soldiers who — to the tune of muffled curses from the non-coms — simply sat down to rest. For a time I shrank from discarding any gear. I could not imagine that our officers would condone this wholesale abandonment of government property. But eventually it became clear that they were unconcerned (indeed none of them was in any kind of "uniform"), and so I began to unload. . .

Along the route of march Hadden abandoned his gas mask, field pack, overcoat and "anything that weighed a little and that I could conceivably do without." Never again would Hadden or his comrades be required to carry every piece of equipment prescribed by Army directives, instead "with the exception of his rifle, helmet and entrenching tool[,] each man was left to his own devices when it came to deciding what clothing and equipment he would keep and what he would do without." [1]

"We try to go as Light as Possible"

Throughout the war the Army tried to give American soldiers the best equipment in sufficient quantities for them to be successful in every battle and, ultimately, win the war. However, the men responsible for literally carrying the fight to the enemy often disagreed with what Army planners deemed essential equipment. A YANK magazine correspondent with GIs assaulting the Pacific atoll of Makin observed:

One of the soldiers aboard was muttering to himself.

"So get the hell across the beach fast," he mimicked the captain. "Just look at me. I'm carrying a pack, a gun, a load of ammunition, two canteens, a radio set, a shovel, grenades and I don't know what all, and 'move fast,' he tells me.

"Scientific war, hell. Every time somebody invents something, they give it to the goddamn infantryman to carry." [2]

The culling of equipment was a universal experience of infantry combat. Colonel James C. Fry noticed that the troops in his regiment fighting in Italy adopted a similar disregard for certain pieces of their issue-equipment after only a few days of combat:

Our first introduction to combat had accomplished a complete change in my soldiers. . . They had discarded items of equipment that, for the moment, were unnecessary. Gas masks and haversacks were nowhere in evidence. . . Pockets sagged from the oblong shaped packages of K-rations, and an extra bandoleer of ammunition swung from each rifleman's shoulder. With a keen memory for the chilly nights they had endured, most men carried a raincoat or blanket tied into a bundle by a pup-tent rope. [3]

To the infantryman, who depended on his mobility for survival and largely operated without the benefit of motorized transport, bulky and unnecessary items like haversacks, gas marks, and mess kits "were simply an impediment and a bore." [4] All infantrymen quickly learned an inarguable rule of modern combat: "Travel light. You've got to carry everything on your back." [5]

Even food and personal items were subject to abandonment. Veteran 4th Infantry Division rifleman Carlton Stouffer wrote to his parents from France thanking them for several packages of food but advised them not to send any more because, "we try to go as light as possible because we often march great distances and often we must move fast so we don't want extra weight." [6]

"Anything you couldn't carry in a pocket you shouldn't be carrying"

While many infantrymen utilized blanket rolls (a blanket and/or half of a canvas pup-tent) and gas mask bags (while the mask was of questionable utility, the canvas carrier was popular as a light pack) to carry sundries, their field jackets, shirts, and trousers provided ample pocket space.

Private and rifleman Lester Atwell catalogued the some of the contents of his pockets as his unit prepared to enter the frontlines around Metz in the autumn of 1944:

Before getting into the narrow sleeping bag, I'd dump anything hard or breakable out of my pockets: crammed wallet; cigarettes in one of those wonderful plastic cases – mine was red –; heavy, dull-bladed scout knife that some day I was going to sharpen; three pairs of glasses, all practically worthless; toothbrush; fountain pen; lumps of sugar; combination tool for the rifle; clips of ammunition; prayerbook [sic]; slips of Nescafe, bouillon, orange and lemon powder; K-ration crackers– everything went into my helmet. [7]

Atwell's pockets, like those of other soldiers, contained items reflective of his military occupation, ammunition and a combination tool for cleaning his rifle, but also more intimate items like a prayer book and several pairs of eyeglasses. Rifleman and 26th Infantry Division soldier Bruce E. Egger, stuffed his pockets similarly, "billfold, paybook, notebook, two boxes of lead*, two tooth brushes, bottle of halazone [water purification] tablets, sometimes as high as eight D-bars [chocolate], three bags of cococa, string, Bible, matches, knife, can opener, and a number of other pieces of equipment, can't hardly call it junk." [8]

Platoon leader Lieutenant Paul Fussell recalled that veteran soldiers "got rid of all but the essentials in our personal kits" and that as a rule, "anything you couldn't carry in a pocket you shouldn't be carrying." Fussell stuffed his pockets with "extra socks and gloves and cigarettes and matches and K ration and toilet paper and letters from home and V-mail forms for writing back and a pen to write with." His pockets also carried his company's mail censoring stamp, because as an officer Fussell was responsible for censoring the outgoing mail of his soldiers, a small New Testament, spoon (his only eating utensil), and food items mailed by his parents (candy, cookies, and jarred Mexican tamales and olives). [9]

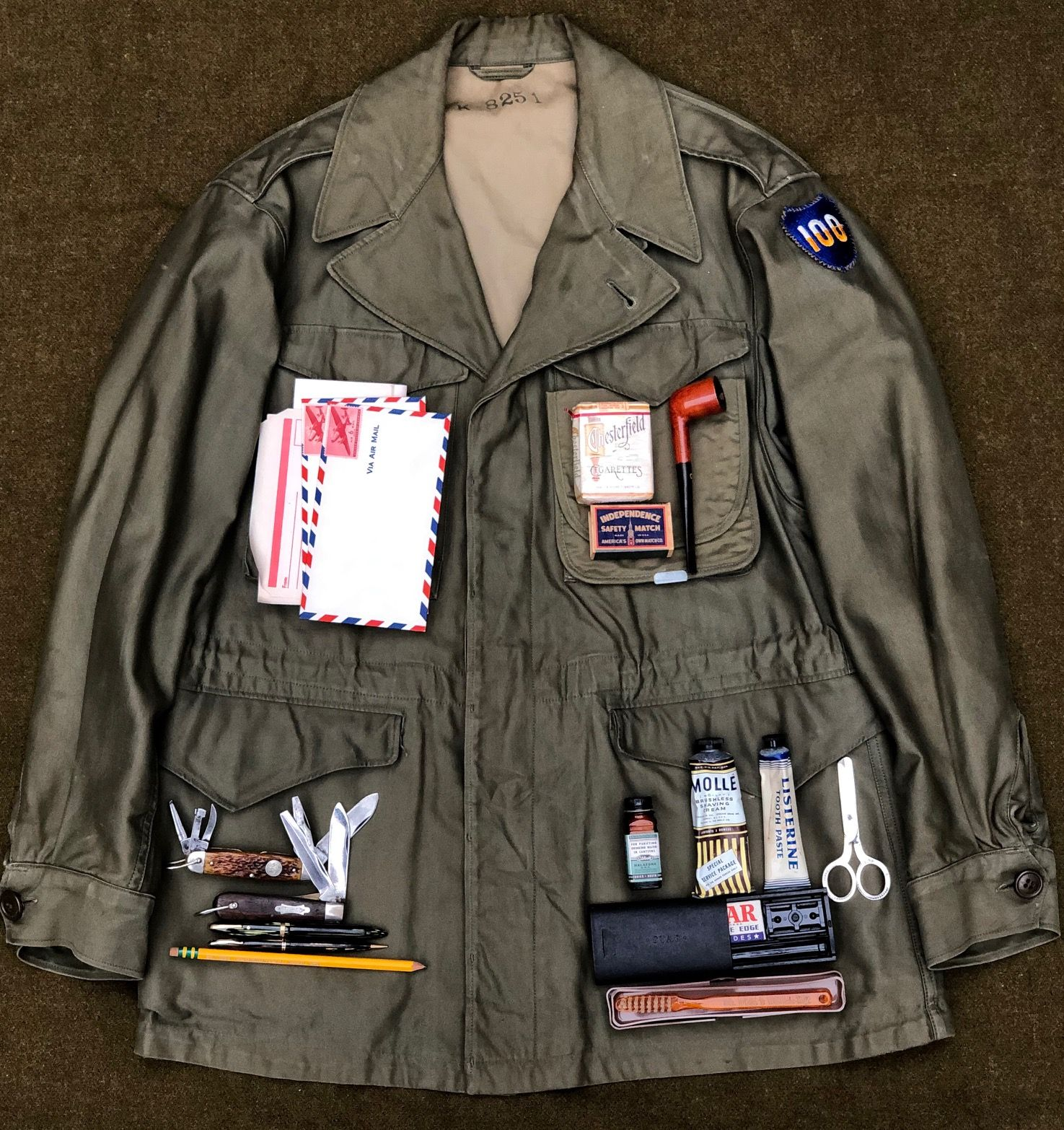

Private First Class Thomas B. Harper III, a soldier in the Communications Platoon of Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 399th Infantry Regiment, 100th Infantry Division, wrote to his parents from the frontline in France in November 1944 about the items he carried in his field jacket pockets:

"Boy do I travel heavy- listen to what I carry in my field jacket. In one pocket I have toilet articles (toothpaste, shaving cream, razor, blades, scissors, tooth brush, and water tablets!). In the other I carry matches, pipe, cigarettes, in another I carry paper, and in the last [,] two pocket knives, pencils and pen- and that's just one garment! [10]

As a member of his infantry battalion's Headquarters Company, Harper may have had more use for toilet articles than the average rifleman closer to the frontlines. In training and combat Harper wrote almost daily to his parents, and so the presence of writing paper is not surprising. The pen and pencils are also indicative of Harper's writing habits, but could also be used to write out radio communications. Pocket knives are utilitarian, but were also necessary for communications personnel like Harper who were issued pocket knives to strip and splice field phone wires (the smaller T-29 knife was issued to all of the members of Harper's platoon).

104th Infantry Division sniper Charles Davis carried a remarkably impressive and diverse amount of items in his pockets. In a letter to his wife he mentioned only a portion of the forty-seven separate items he was carrying while fighting Germans around Merken, Germany:

Wallet, D ration bar of chocolate, gun part, scissors, key ring, map of Germany, pay book, Red Cross coupons, letters, radio book, mirror, your picture (Jean), photo folder, pipe, Testament, fountain pen, stamps, toilet paper, German and Belgian currency, handkerchief, newspaper ["The Stars and Stripes"], needles, German coins, Belgian coins, English half crown, Religious coin, matches, rifle cleaning patches, string, three pocket knives, safety pins, nails, cigarette lighter, thimble, tweezers, salt shaker, [halazone] tablets, screw driver, pencil, Christmas card, pipe tobacco. [11]

The items Davis carried were fairly eclectic, but he considered the most important items, many directly related to his role as a sniper, as: matches, pocket knife, cleaning patches for his rifle, the salt shaker (Davis hated the taste of Army rations), screw driver (useful for disassembling his rifle), scissors, map, mirror, and toilet paper.

Davis admitted "that was an awful bunch of stuff for a man that was trying to travel light," but it shows how much a soldier could conveniently carry in his pockets. [12]

While field jackets and other outer layers were typically the garments with the most pocket space, Captain David Willis, a company commander in the 89th Infantry Division, catalogued over two dozen separate items he carried just in his trouser and shirt pockets in a April 1945 letter to his wife:

In my pockets? Left trouser pocket: blue kerchief, key case with silver dollar, pack of Wrigley's Juicy Fruit's [sic]; right trouser pocket: box of safety matches, two combs (don't ask me why), one pocket knife (good) and one knife with corkscrew (picked that off a German POW), nail file (with out case, BUM) and nail clippers; watch pocket: one round .38 caliber ammo, two paper clips; left shirt pocket: New Testament, rosary, tweezers; right shirt pocket: Sunday missal, small reading glass, three celluloid folders of pictures of you and Mary Lynn; hip pocket, right: billfold plus two letters from you; hip pocket, left: notebook and toilet paper. That's traveling light cuz [sic] I usually have a candle stub, Lifesaver mints, more [toilet paper], C-ration caramels or candy, your bullion cubes, my toothbrush, etc. Walking one-man general store, that's me. [13]

Willis's pocket contents are an interesting mixture of religious items, useful articles, and personal items, all reflective of an average soldier's wants and desires.

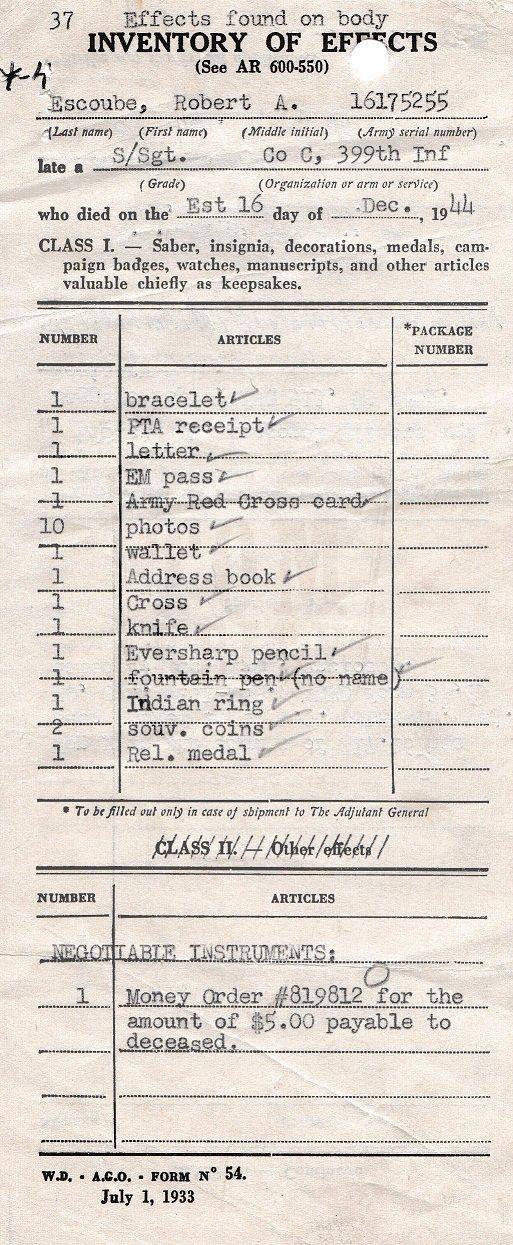

Another source of information on the personal items soldiers carried are "Individual Deceased Personnel Files" (IDPFs). These files, all held at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri, include the burial details of soldiers killed in action during the Second World War. Most files contain a "Inventory of Effects," that details the personal (i.e. non-government issue) items found on a soldier's body at the time of burial. While the contents and details in these documents can vary greatly, they can provide an incredible amount of information on what a particular soldier carried in combat.

Below is the Inventory of Effects of Staff Sergeant Robert A. Escoube who was killed in action in the area of Bitche, France, while serving in the 100th Infantry Division in December 1944. It lists fifteen different items found on his body, including many of those mentioned in the sources examined above: photographs, religious medals, a knife, wallet, and souvenir (foreign) coins.

Left to Their Own Devices

While pocket contents were as varied as the soldiers themselves, even in the small sample of primary sources quoted above there are a striking number of commonalties. For example, writing instruments and stationery, food, cigarettes and matches, pocket knives, and religious items are mentioned in nearly every account. Yet, each also includes specific items that are particular to each soldier, a salt shaker, nail file and clippers, toothpaste, and a plastic cigarette case.

Combat troops learned very quickly to discard equipment they determined to be unnecessary. This reduced their loads to only essential items and allowed them to move quickly on foot, a critical aspect of infantry combat. Memoirs, letters, and IDPFs provide specific details on what average soldiers considered worthy. Those items include Army-issue items, captured enemy equipment, looted civilian items, and mementos, all reflecting particular soldier's military occupations or personal needs.

Footnotes

[1] Alexander H. Hadden, Not Me: The World War II Memoir of a Reluctant Rifleman, (Bennington, VT: Merriam Press, 2012), 96-98. Other memoirs of infantrymen echo Hadden's observations and note that discarded equipment was at times salvaged by their own units and reissued, "the average infantryman had the pockets of his combat jacket crammed with K or C rations, shaving articles, pictures, cigarettes, candy, dry socks, writing paper and pens, and mess kit with spoon and fork. He would have his raincoat folded over the back of his belt or wear it to help keep warm. Also, if we were doubtful as to wherher the trucks would be able to bring up blankets at night, he would carry two to four blankets and a shelter half slung over his shoulder. Any time we had to make a foot march of more than just a few miles the roadside would be strewn with blankets, overcoats, overshoes, and gas masks. A truck would follow along behind us the next day, collect the equipment, and reissue it to us." Bruce E. Egger, et al., G Company's War Two Personal Accounts of the Campaigns in Europe, 1944-1945, (University of Alabama Press, 1992), 119.

[2] "Random Notes on the Makin Operation, From a Reporter's Invasion Diary." YANK The Army Weekly, January 7, 1944, 7-8. Accessed January 10, 2021, https://www.unz.com/print/Yank-1944jan07-00008/

[3] James C. Fry, Combat Soldier, (Washington, D.C.: National Press, Inc., 1968), 43.

[4] Paul Fussell, Doing Battle: The Making of a Skeptic, (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1998), 136.

[5] Bill Mauldin, Combat Tips for Fifth Army Infantry Replacements, (N.p., 1945), 8.

[6] Carlton H. Stauffer, Rifleman : Pfc. Carlton H. Stauffer, 13128357, Pennsylvania State Archives, Manuscript Group 7, Military Manuscripts Collection #365, Miscellaneous Papers of Carlton Stauffer(Accession #2526), 187.

[7] Lester Atwell, Private, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1958), 40.

[8] Egger, G Company's War, 155. *It is unclear if Egger's reference is to boxes of pencil lead, for example for a mechincal pencil, or using the slang meaning of "lead" to refer to ammunition. In the author's opinion, Egger is referring to ammunition.

[9] Fussell, Doing Battle, 136.

[10] Thomas B. Harper III, letter dated November 24, 1944. Author’s collection, 2.

[11] Charles Davis, The Letters of a Combat Rifleman, (Pittsburgh, PA: Dorrance Pub., 2001), 104.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Richard P. Matthews, Good Soldiers: The History of the 353rd Infantry Regiment, 89th Infantry Division, 1942-1945, (Portland, Ore.: 353rd Regimental History Project, 2004), 336.