Co-o-o-o-rpsman! . . . It was a shout without being a shout; it was a wail which denied all the training of the trooper for in it was everything primal: fear, pain, and agonized terror. It was a wail without an end or beginning but somehow it was repeated and how I heard it over the furious sound of the beach I'll never know but I did.[1]

Allen R. Matthews was not a typical Marine, and his book The Assault is not a typical World War II memoir. At 32 years old, the college graduate and former newspaper reporter was the oldest man in his company, a distinction that earned him the nickname "Pop". [2] He volunteered for the Marines in the spring of 1944 and was assigned as a rifleman to C Company, 25th Marines, 4th Marine Division. [3] Matthews only fought in one battle, and was only in combat for twelve days, but his memoir The Assault is one of the best accounts of combat in the Second World War.

"My mind could not conceive the horrors of such a campaign"

Matthews's first and only combat was on the island of Iwo Jima in February 1945 (for more on the battle see my post here). In his naivety before the battle Matthews tried to mentally prepare himself for the worst, but his experience taught him that "my mind could not conceive the horrors of such a campaign."[4]

Landing on the first day of the battle, Matthews's unit was immediately in the thick of the fighting. Matthews was jarred by the experience of being under enemy fire for the first time, and the unexpected ferocity of the Japanese resistance. Battle was a foreign and frightening world:

Those noise was part of our existence as much as were the foul air and the dirty water and the obscene words and the no-food. These were everything and nothing; they were a part of time, but that meant nothing also. For time was now two-dimensional. It had its past which somehow trespassed into the now to become present but there was nothing of the future in our existence. . . Time, the basis of understanding, was a lifetime wrapped in a few days. The years which had gone before were meaningless except for their contribution to sensation: the sudden sharp memory of hot food or the exquisite realization of the meaning of warm water. The future simply was not there, either in our living or our planning.[5]

Shortly after landing Matthews's unit was engaged in securing Hill 382, the second highest point of elevation on Iwo Jima and a Japanese strong point. Hill 382 and the area around it became known as the "Meat Grinder".[6] Repeated attacks against the Meat Grinder were repulsed, and Matthews and his comrades suffered tremendously. The loss of friends, the incessant noise, lack of sleep and sufficient food took its toll:

. . . we were gripped by exhaustion, a terrible exhaustion which turned our muscles to jelly and buckled our knees. And because the fatigue was nervous as well as physical, we were seized by an apathy which obliterated everything but the harrowing necessity of picking our feet up and putting them forward.[7]

By the twelfth day of the battle Matthews was suffering from several superficial injuries as well as mental and physical exhaustion.[8] The last man left from his squad, Matthews was ordered to the rear, his battle over:

So first squad of the second platoon was gone. It was gone, by ones and twos, but irrevocably, and in leaving, each member had removed not only himself but a piece of those who remained behind him. It was a truth never more apparent than in battle. The last of the twelve had been exhausted two days ago and some were dead and some were wounded and some sick and some injured. But they were gone and now I was gone also.[9]

Almost immediately Matthews began writing down his recollections of the battle. While hospitalized he borrowed a typewriter and finished the manuscript for The Assault in just eighteen days.[10]

"Every page rings true"

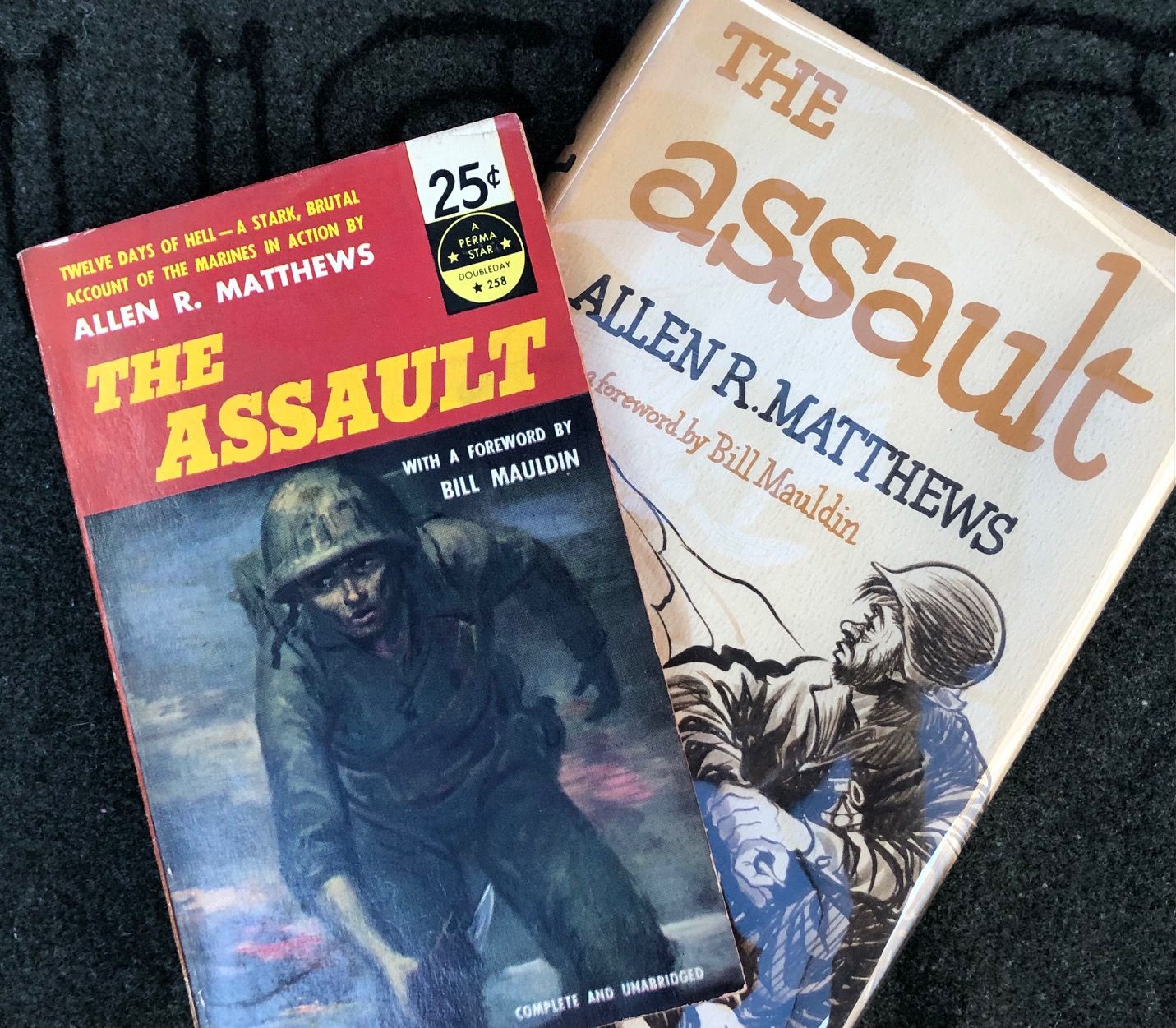

When The Assault was first published in 1947, it included a forward by Bill Mauldin, the acclaimed war cartoonist and author of the widely successful ode to the common foot soldier Up Front. Mauldin praised Matthews's work as an antidote to the rapid onset of public apathy towards books about the war. Direct and vivid, The Assault was just the book Mauldin believed the American public needed to read:

Books which undertake to prove things about war, or to explain big-scale causes and effects, are very important reading for those who take an interest in occurrences outside their own back yards. But just as important are books like this which use plain language and fill in the unwashed, stark, and bitter part of war, in which men kill other men – not for ideals, because men in holes haven't time to think up reasons for being there; and not for military glory, because men in holes seldom know what the strategic plan is even on the other side of the hill; but simply because the men have been put there and in order to keep alive they must kill first.[11]

Matthews's style, in particular his nearly pedantic obsession with the details of his personal battle for survival, also resonated with reviewers. The New York Times described Matthews's writing "as if he were watching himself through some impregnable window in the middle of the battlefield."[12] The Chicago Tribune believed that The Assault was "one of the best answers we have had thus far to the question, 'What was it like?'. . . In fear-frightened prose [Matthews] takes you to the beachhead and then half carries, half drags you from foxhole to foxhole".[13] One reviewer recognized that the literary value of The Assault transcended its subject matter and advised readers, "Don't pick up a copy of 'The Assault' with the attitude it looks like 'just another war book. It's just another war book the way 'The Red Badge of Courage' is just another war book."[14] The Assault even received praise from renowned novelist Ernest Hemingway who called it a "first rate" book.[15]

One reviewer who did know what combat was like, Major Orville C. Shirey, a former intelligence officer with the Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Italy, confirmed what civilians suspected. [16] In his review of The Assault in the Army's Infantry Journal Shirey concluded that "every page rings true", and praised Matthews's work for its accurate telling the combat soldier's story:

While the shooting war was still going on, a lot of us wished we could make the people back home understand what a combat infantryman's life was like: noise, confusion, terrible fear, heroism, brief flashes of action, dragging exhaustion, boredom, and a great many other things that were all mixed up in our minds as combat. The Assault comes as close to telling the combat soldier's story, stripped of heroics and causes, as any book yet published.[17]

"It is still one of the very best"

The Assault was a commercial success, and was one of the ten best selling books in the year it was released. For the second edition, printed in paperback in 1953, Bill Mauldin included a minor but unequivocal addendum to his earlier forward, "It is still one of the very best."[18] Matthews passed away suddenly on July 26, 1957, but The Assault maintained its popularity.[19] Additional reprints followed, the last occurring in 1980, and copies of later editions can usually be purchased for less than $15.

Still, because it has been out of print for several decades and perhaps because it only covers one individual's small part in a single battle, The Assault has gotten less attention from historians and readers than more recently published memoirs, especially those featured in the HBO miniseries The Pacific. That is regrettable because when compared to other Second World War memoirs, like E.B. Sledge's With the Old Breed and Robert Leckie's Helmet for My Pillow, The Assault better conveys the chaos of battle and the visceral fear of the combatants by omitting references to strategies and tactics that are often included in more recently published memoirs to augment gaps in a writer's memory.

As the Second World War recedes further into history, and witnesses to the major events of the conflict disappear, books like The Assault become more important because they speak for thousands of infantrymen who could not or did not leave us records of their experiences. Moreover, The Assault warrants relevance because it so perfectly succeeds in answering the question "What was it like?" by presenting combat as the "foul business full of fear and loneliness and misery" that Matthews and countless others knew it to be.

Footnotes

[1] Allen R. Matthews, The Assault, (New York, NY: Dodd, Mead, 1980), 40.

[2] “Allen Matthews, Writer, 43, Dead; Author of 'Assault,' Novel of Marines in War, Managed Jamestown Corporation.” The New York Times. The New York Times, July 27, 1957. https://www.nytimes.com/1957/07/27/archives/allen-matthews-writer-43-dead-author-of-assault-novel-of-marines-in.html.

[3] “Allen Rabun Matthews in US Marine Corps Casualty Indexes.” Fold3. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.fold3.com/record/643097176/allen-rabun-matthews-us-marine-corps-casualty-indexes.

[4] Matthews, The Assault, 17.

[5] Ibid., 5-6.

[6] Joseph B. Ruth, A Brief History of the 25th Marines, (Washington, D.C.: History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1981), 35-36.

[7] Matthews, The Assault, 211.

[8] “Allen Rabun Matthews in US Marine Corps Casualty Indexes.” Fold3.

[9] Matthews, The Assault, 3.

[10] “Allen R. Matthews Dies: Rites in Georgia Sunday.” Daily Press. July 27, 1957. https://www.newspapers.com/image/231113292.

[11] Allen R. Matthews, The Assault. (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1947), vii.

[12] Charles Poore, “Books of the Times.” New York Times. July 26, 1947, Saturday edition, sec. Sports. https://nyti.ms/3qZXHkb.

[13] Victor P. Hass, “Rough, Tough, Real Story of Pacific War.” Chicago Tribune. June 29, 1947, sec. Part 4. https://www.newspapers.com/image/370934070/.

[14] W.L. Maner, “War's Brutual Realism: Marine Veteran Tells Vivid Story.” Richmond Times-Dispatch . June 22, 1947, Sunday edition. https://www.newspapers.com/image/616084257/.

[15] Matthew J. Bruccoli, and Ernest Hemingway, Conversations with Ernest Hemingway, (Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1986), 50.

[16] Shirey Memorial Scholarship: a JAVA Memorial Scholarship for High School Seniors. Japanese American Veterans Association. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://java-us.org/resources/EmailTemplates/Shirey%20Scholarship%20Profile/index_preview.html.

[17] Maj. Orville C. Shirey, “Unimpeachable Account of Battle.” The Infantry Journal, August 1947, 57. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Infantry_Journal/K4HpAAAAMAAJ

[18] Allen R. Matthews, The Assault, (Garden City, N.Y.: Permabooks, 1953), 7.

[19] “Allen R. Matthews Dies: Rites in Georgia Sunday.”