T. Grady Gallant, a Marine who landed on Iwo Jima with the 4th Marine Division, remembered its conquest as "a terrible battle: awful in its intensity, its concentration, and its suffering."[1]

The fighting on Iwo Jima was some of the most ferocious of the entire Second World War. It was also an anomaly of the Pacific Campaign because it was the only battle in which American casualties exceeded those of the Japanese.[2] In fact twice as many Marines were killed on Iwo Jima than in all of World War I.[3]

The iconic flag raising most associate with the battle, far from being a signal of ultimate victory, occurred on the fourth day of the Marines' attack and was eclipsed by fighting that would continue for another month. Rather than squander manpower in fruitless counterattacks, the Japanese defenders conducted "an intelligent, passive defense from successive highly organized positions . . . and fought to the bitter end."[4] The extent of that defense was incredible. An official Marine Corps report of the battle notes that in one 800 yard area, as many as one thousand mutually supporting underground blockhouses, bunkers, pillboxes, and caves were destroyed by attacking Marines.[5] So brutal was the 36-day conquest of the island that it cost approximately 695 American lives per square mile, and that figure more than quadruples when Japanese casualties are included.[6]

Navy corpsman Richard E. Overton served as a medic in D Company, 26th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division on Iwo Jima. It was his first and last combat and the experience had a profound impact on him. While garrisoned in Japan after the war Overton began to record his memories of the battle, in part to better understand what he had endured.[7] Those notes became the basis of his memoir, God Isn't Here: A Young American's Entry into World War II and His Participation in the Battle for Iwo Jima.

In God Isn't Here, Overton captures the intensity of the battle and mental strain it placed on him and his comrades:

The constant explosions from shell fire had a terrible psychological effect upon us. There was always the present expectation that the next shell would wound and dismember us.

Under the constant and sustained exposure to this threat the mind seems to disengage itself from relationship with the physical body. At first there is excitement as the adrenaline enters the bloodstream and then comes the terror. As the exposure continues and the senses begin to dull. The mind will eventually not perform, and the body cannot act.

There were times during which I could not control or organize my thoughts. My stomach felt like jelly was rolling around inside of it. I could touch my hands to my face and could not feel the contact. I watched my foxhole companions go through the same experience. Their jaws would slacken allowing their mouths to open while saliva ran out of the sides and down their chins. Their eyes would lose all sign of emotion and apparently what they were seeing was not registering in their brains. [8]

Overton served in D Company throughout the Iwo Jima campaign but succumbed to mental exhaustion or "combat fatigue" when his unit was finally placed in reserve a week before the island was declared secure.[9]

I tried to eat cheese and crackers from a K ration and found it tasteless and discovered I couldn't swallow the food as it just kept falling out of my mouth and spilling down the front of my blouse. Even the water I tried to down refused to enter my through and merely ran out either sides of my mouth. I lay back on the sand and tried to shut my eyes. They wouldn't close and I felt frightened as I couldn't understand what was happening to me.[10]

Unable to eat, drink, or speak, Overton was ordered off of the island by a Navy doctor to recuperate. He was one of over 2,600 Americans treated for combat fatigue during the battle. [11]

Overton returned to Iwo Jima in 2000 and reflected on the scars he and the island shared:

Its surface is covered at present with a dark green cover of brush that reaches eight feet in height. Close scrutiny of the ground beneath the bush reveals that its surface is still marred by the action of battle. Still visible are the outlines of fox holes, tank traps, shell craters and the broken remnants of concrete bunkers. Time, helped by wind and rain has worn down the jagged edges of such things, but then they are only the scars of what once was. . . As I viewed the island it came to my mind the similarity between what I viewed there and the state of my own mind. The damage to both is still there, but is now hidden by scars or by a facade which only give the impression of being healed. [12]

Ultimately the return to his old battlefield was able to give Overton some solace. In closing his memoirs he wrote, "I am allowing the ghosts still present there, to occupy the island for themselves, to the end of time." [13]

Further Reading and Watching

For those interested in how servicemen suffering from combat fatigue received medical treatment, the U.S. National Archives has restored and posted the 1946 film, "Let There Be Light" on YouTube.

Additionally, both volumes of the Army's official history on the subject, Neuropsychiatry in World War II, are available for free on the U.S. National Library of Medicine digital library here and here.

Footnotes

[1] T. Grady Gallant, The Friendly Dead, (Garden City, NY : Doubleday & Co., 1964), ix.

[2] Robert S. Burrell, Ghost of Iwo Jima, (College Station, TX : Texas A&M, 2006), 82-83.

[3] Gallant, The Friendly Dead, ix.

[4] Special Action Report, Iwo Jima Campaign. Headquarters, V Amphibious Corps. May 13, 1945, 5. http://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p4013coll8/id/1153/rec/14

[5] G-3 Report of Planning, Operations: Iwo Jima Operation, Enclosure E. May 1, 1945, 2. http://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p4013coll8/id/2150/rec/3

[6] Gallant, The Friendly Dead, ix.

[7] Richard E. Overton, God Isn't Here: A Young American's Entry into World War II and His Participation in the Battle for Iwo Jima, (Clearfield, UT : American Legacy Media, 2006), 7.

[8] Ibid., 243-44.

[9] Ibid., 300.

[10] Ibid., 277-78.

[11] Burrell, Ghosts of Iwo Jima, 83.

[12] Overton, God Isn't Here, 326-27.

[13] Ibid., 327

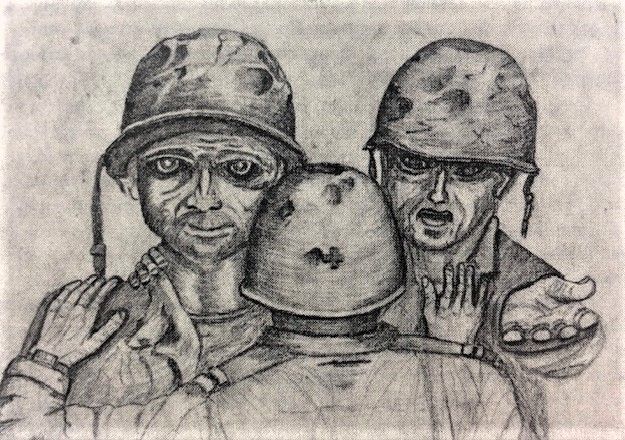

[14] The cover painting is The 2000 Yard Stare by Tom Lea, depicting a United States Marine during the battle of Peleliu. "Thousand Yard Stare," Wikipedia, accessed February 13, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thousand-yard_stare.