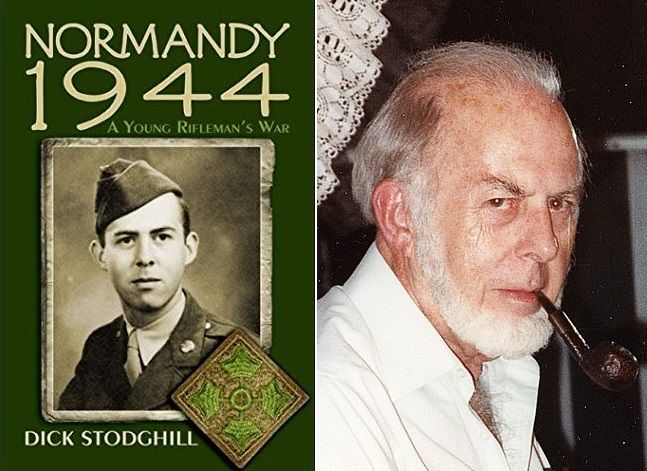

Dick Stodghill arrived as a replacement infantry in G Company, 12th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division shortly after the Normandy landings. His memoir, Normandy 1944: A Young Rifleman's War, details his experiences fighting in the Norman bocage. Stodghill once flippantly described his memoir as "a book devoted to war and killing and watching your friends die," but it is certainly one of the best pieces of writing to emerge from the Second World War. [1] I believe the excerpt below, titled "Casualty Rolls" is on par with Ernie Pyle's acclaimed "The Death of Captain Waskow" because of its ability to convey to the reader a profound sense of gravity and loss.

Casualty Rolls

They were stacked high along a stone wall across a side street from Pasteur Hospital, an even one-hundred and fifty of them resembling oversized khaki colored sausages. These were the casualty rolls, a mute testament to the savage fighting on the road to Cherbourg.

No one had returned to claim them when the rest of us walked along the rows of blanket rolls laid out in military precision on the ground, each man seeking his own among the many that in appearance were markedly similar. When everyone had picked up a roll containing all his possessions other than those on his back, we stood off to one side waiting to be told what to do.

Then, as was always the case, the rolls remaining on the ground underwent a transformation. They had been blanket rolls, now they were casualty rolls. With the new name came a new look, one that spoke of infinite loneliness, lost hope, shattered dreams.

Someone had to open these pathetic reminders of lives that a short time before had been robust. The GI equipment had to be separated from the personal belongings and then formed into piles, shoes here, pants there, a different stack for every item issued by the Army. Small cardboard boxes waited for what was left: bundles of letters in feminine handwriting, photographs of smiling girls, sometimes on of the young children. A fallen man’s memories of another time and another world. Shaving gear, a candy bar that would go uneaten, a paperback book that would never be finished, a spare pair of eyeglasses, a harmonica, the sparse possessions that made every roll unique, gave it the stamp of individuality, the mark of a man who had not returned to claim it. . .

In Cherbourg the unpleasant job of opening the casualty rolls fell to Mike Spinelli and me, a pair of 18-year-old rifleman from Northeast Ohio. It was a job no one wanted, one that would spoil an otherwise sunny and pleasant day for two young soldiers who would rather have been doing almost anything else.

This was not the first time that G Company casualty rolls had been opened. Near Montebourg, about seventy-five others had been processed. Roughly two hundred twenty-five in three weeks of combat, more than the number of G Company men in the third wave to hit Utah Beach on D-Day.

Donald Lewis, the weapons platoon sergeant, was in charge of the detail. He handed Mike a clipboard with several sheets of paper containing typewritten names and serial numbers. Following each name was one of the three sets of letters: KIA, WIA, MIA – killed, wounded, missing in action. The many names followed by KIA were a mute testament to the bitter fighting during those three weeks. Others were listed as MIA – men buried under the dirt hurled by exploded shells and as yet unfound, a few vaporized when a shell hit, other who might have surrendered.

After giving us the few instructions we needed, Sergeant Lewis said he would be in a small room opening off an alley at the far end of the wall. He told us to bring the roll of a man he named back to him without opening it. . .

Sergeant Lewis came by to check on us. We had placed personal items for shipment home in a number of little boxes so Lewis looked them over. He was not happy. From one he took a bundle of letters and tossed them at my feet. 'Look at the return addresses' he said. All were from girls in England or living in towns near camps where the 4th Division had been stationed in the States.

'Going to send those back to his wife, are you?' said Lewis. 'That should make her feel damn good.' From another box he took a pair of eyeglasses, holding them out to me by a thumb and one finger. 'Do you think his mother and father will want these for something to remember him by? Anyway, they’re GI issue.'

He had a few more caustic comments before going back to the alley. His message was received. When the job was finished there wasn’t a single item in any of the boxes. . .

When in late afternoon we came to the roll that Sergeant Lewis wanted to open himself I took it back to him. A little later a question came up and I returned to the alley. When I opened the door of the small room I saw the contents of his friend’s roll spread out on the floor. Lewis sat bent over them, hands covering his face. I quietly closed the door and went back to where Mike was working. The question, whatever it had been, no longer seemed important. [2]

Epilogue

After World War II Stodghill was recalled for service during the Korean War and worked for a short time as a Pinkerton detective, but he was best known as a journalist for the Muncie Evening Press and as an author of mystery stories. [3] Dick Stodghill died on November 7, 2009 at the age of 84. [4]

If you are interested in learning more about Dick Stodghill, you can still access his blog, which was kept up to date until four days before his death, at <https://stodg.blogspot.com>.

Footnotes

[1] Dick Stodghill, "Normandy 1944 - The Book's Finished, But Not War," Stodghill Says So. August 6, 2006, http://stodg.blogspot.com/2006/08/normandy-1944-books-finished-but-not.html (accessed October 10, 2019).

[2] Dick Stodghill, Normandy 1944: A Young Rifleman's War (Baltimore, MD: Publish America, 2006), 88-94.

[3] Dick Stodghill, "My Profile," Blogger.com. https://www.blogger.com/profile/12680444362839182041 (accessed October 10, 2019); John Carlson, "Writer Dick Stodghill Dies at age 84," Hoosier State Press Association, November 19, 2009, https://www.hspa.com/PDF_Publisher/11_19_09_Publisher.pdf (accessed October 10, 2019).

[4] Carlson, "Stodghill Dies", 2, 4.